Resilience of the Commons: observing “resilience” in the governance of decentralised technology communities

Kelsie Nabben & Michael Zargham

June 4, 2021

Suggested reference:

Nabben, K., & Zargham, M., “Resilience of the Commons: observing “resilience” in the governance of decentralised technology communities”, Substack, 2021. Available online: https://kelsienabben.substack.com/p/resilience-of-the-commons-observing.

Introduction

Decentralised technologies are both an assemblage: a construction of social and technical bits to form a functional whole, and an assembly: a storage of data, a record of history, and a coming together to create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. An example of this is blockchains, which are configured of software code, developers, “miners” that validate transactions, “DApps” (decentralised applications) on top of protocols, and user communities. When it comes to ensuring the resilience of these socio-technical digital infrastructures, how can a community of people adapt and recover in crisis? This post discusses resilience as “adaptivity and recovery in response to threat or crisis” in decentralised information systems as a means to understanding how workable social and technical outcomes can be pursued. We draw on an ethnographic case study of a “Gitcoin” funding round under attack to observe how the community leverages governance processes to enact social and technical adaptations towards common goals. We observe the tensions between human and automated evolutions to surface key concerns in sustaining blockchain commons, with persistence of the purpose of the community, rather than the project or protocol, as the goal. These findings have important applications to better understanding the opportunities and limitations of decentralised technologies in facilitating participatory, digital communities.

What are “Commons”?

“Commons” can be described as “the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society...that groups of people (communities, user groups) manage for individual and collective benefit.” (Wikipedia).

Based on this understanding, we are interested in the human aspects of “commons” that are mediated and facilitated by decentralised technologies. In a current research project, Kelsie is investigating “resilience” in decentralised digital infrastructures. Resilience in socio-technical systems is “adaptability and transformability of a system in response to threat or crisis” (Tantri & Amir, 2019). Kelsie is specifically interested in not just the technical adaptations but also the cultural and social outcomes of decentralised systems. She refers to this approach of people as the referent object of security in a digital system as “people security”.

How are blockchains “Commons”?

Public blockchains have been repeatedly referred to as “commons”. This is evident in several characteristics of blockchains. They are socio-technical systems, comprised of both social and technical components. Public blockchains are also “permissionless” resources, meaning it is open to participate in the use, building, or adaptation of the protocol. Blockchains are also an infrastructural base, meaning that they are tools which take on meaning in the context in which they are used and are inseparable from this context (Star, 1999).

Blockchains as a “Ship of Theseus”

In this way, blockchains are analogous to the Greek legend of the “Ship of Theseus”.[1] The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that raises the question of whether an object that has had all of its components replaced remains fundamentally the same object” (Wikipedia). The thought puzzle was discussed by numerous ancient philosophers.

“The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned from Crete had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their places, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same.”

— Plutarch, Theseus

Public blockchains are modular in nature, comprised of open-source software code and composable social and technical components, including software code, developers, “miners” that validate transactions, “DApps” (decentralised applications) on top of protocols, hardware, individual users, communities, and the ledger data as a shared record of history. Whilst any of these components can be replaced, including “forking” the ledger of transaction history itself or transition from a “proof-of-work” consensus algorithm to a “proof-of-stake” consensus, the blockchain is a persistence, functional whole.

The legend of the Ship of Theseus is often applied as a question of the persistence of identity over time. I would like to propose here, that it is also a question of resilience, in asking, which social and technical components of a decentralised infrastructure must persist for it to be considered resilient?

This question can be explored through a case study on a decentralised technology project responded to an external threat. In this paper, I have chosen to investigate “Gitcoin”, a popular shared goods funding mechanism in the Ethereum blockchain community.

Funding common resources as a blockchain commons

Gitcoin performs an important function in the Ethereum community, in providing a mechanism for the community to coordinate on funding projects, as shared infrastructures and commons goods that are perceived as important to the overall growth of public, decentralised blockchains. Yet, this responsibility for funding “public goods” did not always lie with Gitcoin.

Gitcoin was preceded by a number of shared funding mechanisms in the Ethereum community. An early instantiation of this was “The DAO”, an attempt at a fully automated blockchain-based solution for pooling and allocating capital to fund projects. The DAO was a short-lived experiment due to a dismal hack, which occurred due to a simple error in the software code and allowed 3.6 million ‘ETH’ tokens (or $50 million at the time) to be drained from the smart contract. This was followed by The Ethereum Foundation, whose “Ecosystem Support Program” (ESP) which maintains a “wishlist” of tools and projects which have surfaced as priorities which they would like to allocate funding to. Although it continues to exist, the ESP is under continual iterations to improve its service offering, as somewhat of a manual, bureaucratic process to surface priorities, fairly judge proposals, and include the entire Ethereum ecosystem. There was also the “Ethereum Community Fund” (ECF). ECF began as an infrastructure grant program, supported by some of the world’s leading Ethereum projects in the wake of the Initial Coin Offering boom of 2017. The initiative quickly collapsed into internal politics, as projects failed to commit promised capital and resolve transparency and governance issues on how funding was allocated. It has since evolved into a separate funding platform.

Gitcoin itself is a hybrid of human and automated processes. Through a semi-automated process, people can submit a project for a grant, and others can register an account, donate cryptocurrency, and vote for the project that they would like to see funded. The “crowd sourced intelligence” of the mechanism has successfully surfaced matters of importance to the community, which previous approaches undervalued, such as community education.

The projects with the most votes receive “matched” funds from a shared donation pool, adding to the reward for a high numbers of votes, in a process known as “quadratic funding”. The most recent round consisted of 168,000 donations, totalling $1.38 million, which was matched by a further $500,000 in funding.

Commons under threat: Gitcoin Grants Round 9

Bruno Latour describes all technology as having embedded “scripts” that set norms and mediate behaviours. The script of Gitcoin is “we are a fair, legitimate, public goods funding mechanism for the Ethereum community”. For Gitcoin, this sense of “fairness” is achieved through the transparency of the donation process and decentralisation of decision-making. Yet, socio-technical systems are inherently complex, meaning that behaviour can go “off-script”.

Gitcoin grants round 9 was subject to a “sybil attack”, in which users created “bots” to create multiple, fake identities and spam the grants round with numerous micro donations to some projects. This attack ruined the matched funding allocation mechanism, as donations no longer signalled genuine community interest in supporting the projects that they think are the most important.

The attack is thought to be due to a misalignment of incentives, as a consequence of free cryptocurrency token donations in previous rounds, from projects wanting to “thank” donors for their contribution. It is thought by the Gitcoin team and the community that this motivated people to hijack the system, in the hopes of getting rewarded for each vote in cryptocurrency, after the round. The script became “how can I benefit most from this funding mechanism”. This meant that the Gitcoin team had to pay out the grants round, without knowing which grants were fake, and how to allocate the matched funding pool fairly. The vulnerability here was not only to the grantees and the donors, but to the persistence of Gitcoin as the premier funding mechanism for Ethereum goods and infrastructure.

This vulnerability in the identity layer of quadratic systems was known so in some ways, it was only a matter of time before the system was gamed. Furthermore, as the value flowing through Gitcoin grew to more significant funding amounts being facilitated by the Gitcoin mechanism, sybil attacks were more likely, despite the identity solutions in place to try to verify uniqueness of donors.

Threat management

An intervention was immediately developed, which involved both social and technical adaptations. Key stakeholders involved in developing this response included the Gitcoin team, systems engineering contractor “Blockscience”, and broader community members that were identified due to their active participation in, or critique of, the Gitcoin process.

BlockScience developed “a framework for deterring adversarial behaviour at scale”, involving “defining” adversarial behaviour, detecting it using a machine learning process, human evaluation of detected events to delineate and judge the circumstances of the behaviour, and sanctions to apply appropriate recourse to the issuers of adversarial behaviour.

The crisis surfaced normative tensions about the place human governance processes in a community that espouses value for decentralisation as “trust in code”, through the inability for political or architectural hierarchy or co-option of a system. The crisis response was an inherently subjective, human process. The scripts of Gitcoin and Ethereum community norms needed to be defined in order to be encoded into the behaviour detection framework. We see the communities’ aspirations for “self-governance”, as independence from external influence emerging in conflict with the necessity of human interventions in crisis, to ensure the social and technical functioning of the system adapts and responds for the ongoing survivability of the funding mechanism itself.

Ethereum’s founder, Vitalik Buterin reflected on the Grants round, stating that “some ongoing reliance on centralized moderation will be required, though hopefully this can be simultaneously reduced and made more accountable to the community.”.

Gitcoin completed the pay-out of the funding round by running two alternative scenarios of the amounts that would have been paid to projects with and without the attack, as they chose to absorb the cost of paying out an additional $33,000 so no one could criticize them for judging what was and wasn’t a fair judgement of behaviour. This path of least resistance appears to have satisfied the expectations of the community, for continual participation in the funding mechanism. The process included the good faith gestures from Ethereum’s founder, Vitalik Buterin to signal the credibility of the round, such as participation in ad hoc crisis “Council” and public endorsement stating: “A major success, but also a lot of interesting challenges in this round that will continue being relevant long into the future.” (Vitalik).

“Exit” to DAO

Post crisis, Gitcoin has announced that they are becoming a “Decentralised Autonomous Organisation”. This is being done through the issuance of ‘governance’ tokens to community participants. Governance tokens allow the community to vote transparently on the blockchain (“on-chain”) on decisions relating to how the GitcoinDAO treasury is allocated.

Deferring decisions to “the community” is seen as becoming more “decentralised”, and thus, sustainable and legitimate. “Gitcoin’s choice to decentralize our platform’s governance to a DAO will fully empower the community to govern itself.” (Gitcoin). In this way, we see decisions deferred away from the Gitcoin team, and to the community via software code, machine learning algorithms, and “automation” as a means for maintaining community participation. These evolutions in the Gitcoin project are to sustain the long-term function of the funding mechanism, or in other words, keep the ship sailing.

This “exit to community” is a long-term strategy for the community to co-own and co-govern the stewardship of funding goods that are seen as important to the Ethereum blockchain ecosystem. Yet, the “exit to DAO” also reveals a multiplicity of drivers and incentives, in that while 15% of governance tokens are retroactively allocated to those who have participated in Gitcoin in the past, 35% are time locked for the “team, investors, future employees, and strategic partners of Gitcoin”. The Gitcoin team has made numerous efforts to remove themselves from being seen as a centralising force over decision-making to conduct a fair process in the exit to DAO. This includes abstaining from the GTC delegation process of appointing stewards or becoming stewards, as well as placing team tokens under a vested time lock. This places responsibility onto the initial 15% allocation to community members to set sustainable governance processes before more token unlocks. The challenge of bootstrapping decentralised projects, which Gitcoin itself aims to address, is again raised, in the artificial tension between decentralisation from human involvement, and human governance processes as drivers of sustainability and survival.

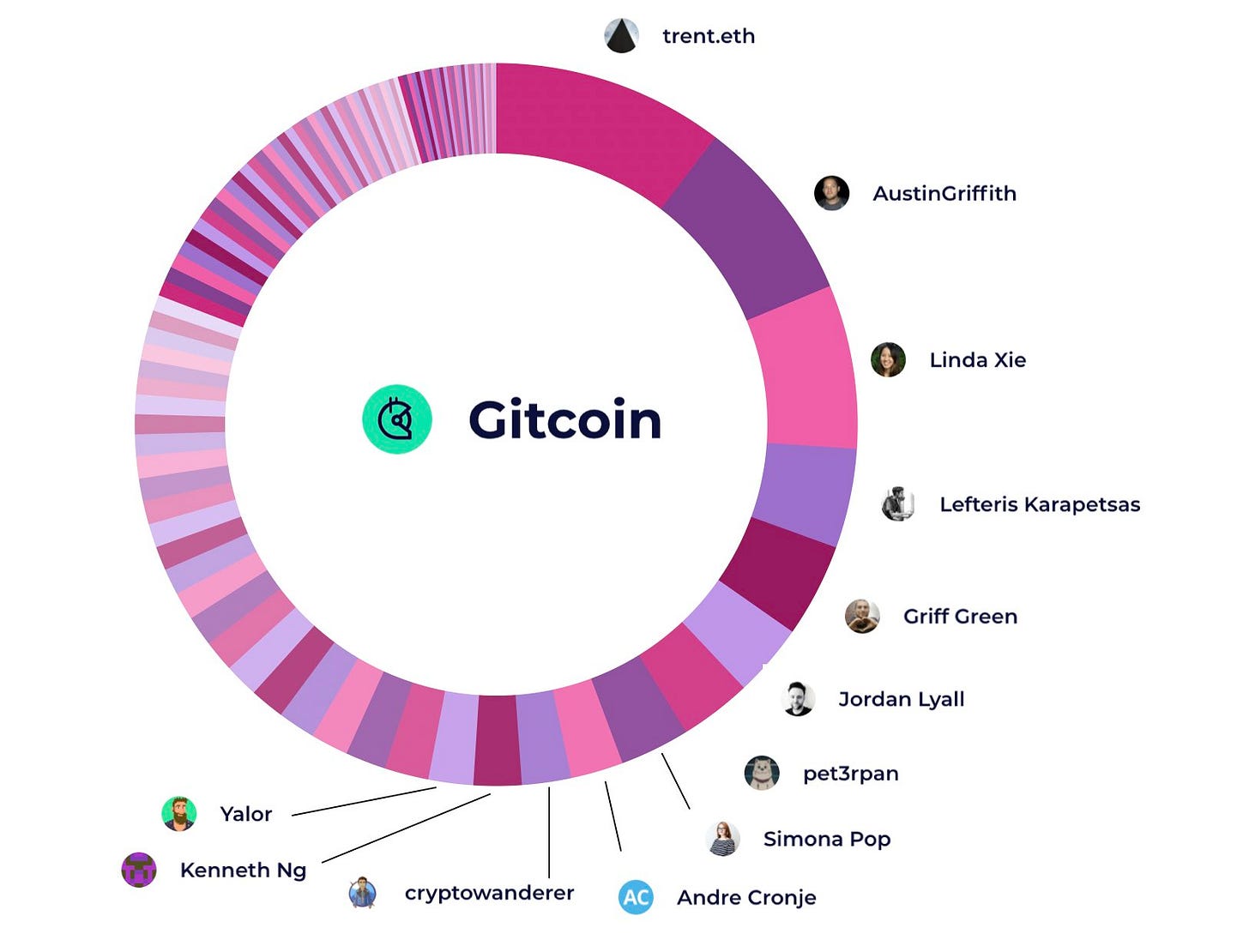

Now, the GTC token holders (from the 15% retroactive airdrop to past donors and applicants of Gitcoin grants rounds that are deemed to form “the community”) can “delegate” their tokens to applicants that they deem worthy of being the “community stewards”. In this way, we see that exit to DAO solves some concerns of centralisation and potential politics but introduces new vulnerabilities and possible attack vectors. Well known crypto-Twitter personalities could engage in coercive practices, such as bribery, in order to receive and maintain GTC token allocations. Then, proposals require the vote of these stewards, who could change the rules in order to serve their own interests in maintaining power and influence in the system. Thus, decentralised digital governance still relies on the human processes of governance. The token delegation process heavily relies on GTC holders understanding the purpose of Gitcoin, and their role in governing it, to decide how best they should delegate their GTC tokens for the GitcoinDAO to be well stewarded.

“The first open source congress of Gitcoin” by Alex van de Sande, (referred to by CEO of Gitcoin Kevin Owocki as “my new bosses”.

Governance, even that of the decentralised variety, surfaces politics. All infrastructure is political, whether it is through human involvement or the rules that humans encode in systems. How this interplay between the social and technical entanglements of decentralised systems and their politics can be leveraged by the incentives and transparency that blockchain-based systems afford, remains to be observed.

Blockchain Commons in “The Next Phase of Growth”

1. Blockchains are Commons that organise around a purpose, not a protocol

We also see that blockchain infrastructures form a community “commons” around a specific purpose, rather than around a particular protocol or project. Blockchains operate as a socio-technical infrastructure, rather than as individual projects or protocols, which comprise replaceable modules of a functional whole.

As Buterin reflected on Gitcoin grants round 3 in 2019, “Ultimately, every mechanism for allocating resources, whether centralized, market-based, democratic or otherwise, must stand the test of delivering results, or else sooner or later it will be abandoned for another mechanism that is perceived to be better, even if it is less philosophically clean.”.

Gitcoin has undertaken a metamorphosis to transform from a project, into a more decentralised “DAO” institutional structure, yet it is the same ship. This institution requires effective governance, according to the norms and values of blockchain communities. The most suitable path goes beyond a specific token allocation, protocol, or governance model, towards how to achieve the broader aims of the community. This shifts the focus away from “becoming a DAO” or “decentralisation”, and towards legitimacy via participation and resilience as the ability for the community to continue to function. This means that the “purpose driven tokens” of blockchain commons are actually about facilitating the incentive mechanisms for “purpose driven communities”.

2. Both social and technical governance is essential for resilience

When a decentralised infrastructure was under threat, both social and technical governance interventions emerged as key drivers of the necessary evolutions for resilience. The Gitcoin mechanism has survived another round, despite the sybil attack. The team and governance processes surrounding the funding mechanism have had to adapt significantly, with the entire project transforming into a “Decentralised Autonomous Organisation” to distribute decision-making responsibility away from the core team and into the wallet addresses of the community. Furthermore, technical adaptations have occurred with the introduction of governance tokens are being issued for on-chain voting to manage the allocation of on-chain donations, as well as the introduction of machine learning processes to flag what could be adversarial behaviour to detect and evaluate attacks in future.

Governance emerges as crucial in guiding evolutions for resilience for survivable systems. As socio-technical infrastructures, decentralised technology communities must acknowledge and embrace transparent governance practices and interventions if the communities themselves are to succeed. These findings can be extrapolated to other contexts of governance in and through digital infrastructures, for legitimate, resilient, semi-autonomous community organising, although in what portions for certain contexts they need to be constructed remains an open area of research.

3. The search for self-governance via digital means is not new

We also see that the desire for online communities to have the mechanisms for self-governance is not new. Blockchain communities are an active grounds for experimentation towards more resilient ways for communities to do this.

Author Howard Reingold has been experimenting with the governance of online communities since the 1980s, having been part of such foundational communities as “The WELL”. Reigngold refers to the work of Nancy White to emphasise key lessons for online community governance, including “make it as simple as possible”, “make sure the needs and purpose of the community (and community owners) are articulated”, and “consider that sometimes benevolent dictatorships are good solutions”.

The tensions between the role of people and the role of automation in governance processes is an open area for further exploration, in terms of allocating responsibility and accountability in these infrastructures in a transparent manner, in order to sustain pursuit of their purpose. Blockchains present both opportunities to enact this transparency, and limitations as a “be all and end all” solution.

Contributors to adaptive capacity for resilient, decentralised digital infrastructures

This write up is intended as a reflection, both to those inside the community on emerging themes to help them make more informed decisions, as well as a means to draw broader lessons that are applicable to the topic of resilience in digital infrastructures more broadly. The interventions of the Gitcoin team, it’s immediate supporters and funders, and the Ethereum community on both governance processes and technical functionality has afforded adaptative capacity for the mechanism to evolve and transform to numerous feedback and attacks.

In its historical context of Ethereum community funding mechanisms, Gitcoin has been a success. The project has outperformed numerous prior attempts at providing this function and is now entering its 10th funding round.

It appears that the biggest threat that the Gitcoin team perceives is illegitimacy via being seen as centralised in their decision making and control over the project. Yet, the involvement of the Gitcoin team has been crucial in bootstrapping the project, and guiding its development and evolution towards more transparency, accountability, and community participation.

Three themes have emerged as crucial in the adaptive capacity of Gitcoin:

1. Transparency: the Gitcoin team seems to genuinely want to share decision making responsibility and communicate how this process is occurring in line with the norms and expectations of the community.

2. Community participation: public social signalling and enduring participation of projects and donors has allowed the function to persist.

3. Evolutionary capacity: with an ability to create, sustain, and absorb feedback, the Gitcoin project has on-boarded criticism and feedback from the community. This will be integral, and perhaps more difficult, for the GTC token holders and the revolving delegations of community stewards, unless addressed explicitly.

How and when “decentralised” projects should “exit” to more decentralised forms of governance, and what, if any, is the right balance between human contributions and algorithmic automation remains to be investigated.

Conclusion

Using decentralised technologies to organise does not mean organising outside of governance. This research has surfaced the tensions in balancing human and automated approaches in governing participatory, online systems in the desire to “decentralise”. Both history and recent events in funding common goods in the Ethereum ecosystem reveals a narrative of this tension between the role of humans and the role of machines in governing blockchain infrastructures, with the aim of continuity of purpose. The most valuable governance tool to generate public trust in the attack on Gitcoin was efforts towards transparency to ensure ongoing community participation, showing that resilience is the adaptive capacity of the community to threat or attack, rather than just a specific governance mechanism or decentralisation via certain computational mechanisms. This research finds that for decentralised technology systems to continue to function, they rely on both human governance practices, as well as the transparency that blockchains can provide. The governance processes designed to mitigate crises are formulated through a combination of collective, human value-judgements and decision-making from key participants in the community, as well as automated processes. Yet, these automated processes still require human design and decision-making to encode the governance rules of the system. This demonstrates the interdependencies of human and machine components in decentralised technology assemblages. We find that the resilience of decentralised infrastructure relies on transparent governance practices that align with community values, for continued participation in the system towards a purpose, rather than in a specific project. This framing of resilience in blockchain commons as online community governance allows us to draw on lessons from the past on approaches to digitally mediated self-governance.

We are excited, and grateful to be involved and be providing feedback as we observe the trajectory of the GitcoinDAO, and continue to research if DAOs are a resilient form of community governance, and if so, what aspects of this infrastructure make it resilient?

[1] See also Kevin Werbach on “the siren song” in “After the Digital Tornado”.

Acknowledgements:

With acknowledgement to the Blockscience team (listed + Burrrata & Jiajia), for ongoing research collaborations, as well as the Gitcoin team (Kevin Owocki & Scott Moore) for taking the time to provide comments.

As always, my work on “resilience in decentralised infrastructures” is developed with the ever valuable supervision of Professor Ellie Rennie and Professor Chris Berg, as well as regular engagement with colleagues at the Blockchain Innovation Hub at RMIT University.

References:

Distribution Q&A”. Available online: https://gov.gitcoin.co/t/gtc-distribution-q-a/3253. Accessed 29 May, 2021.

Alleyne, M., Canon, C., Evans., A., Feng, Y., Schneider, N., Zepeda, M. Exit to Community: A Community Primer. University of Colorado Boulder, Media Enterprise Design Lab. Available online: https://www.colorado.edu/lab/medlab/2020/08/31/exit-community-community-primer. Accessed 1 June, 2021.

Buterin, V. “Gitcoin Grants Round 9: The Next Phase of Growth”. Available online: https://vitalik.ca/general/2021/04/02/round9.html. Accessed 20 May, 2021.

Buterin, V. “The Meaning of Decentralization”. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@VitalikButerin/the-meaning-of-decentralization-a0c92b76a274. Accessed 2 February, 2020.

Distruptionjoe. “Token Engineering Open Science Program: A Multidisciplinary Study of Gitcoin Grants”. Gitcoin blog. Available online: https://gitcoin.co/blog/token-engineering-open-science-program-a-multidisciplinary-study-of-gitcoin-grants/. Accessed 1 June, 2021.

Ecosystem Support Program Team. “Ecosystem Support Program: Allocation Update”. Ethereum Foundation Blog. Available online: https://blog.ethereum.org/2020/04/01/ecosystem-support-program-allocation-update/. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Ecosystem Support Program Team. “Ethereum Foundation Spring 2019 Update”. Ethereum Foundation Blog. Available online: https://blog.ethereum.org/2019/05/21/ethereum-foundation-spring-2019-update/. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Emmett, J., Nabben, K., Bernardineli, D.L., Zargham, M. “Deterring Adversarial Behavior at Scale in Gitcoin Grants: A Framework for Community-Based Algorithmic Policy Making”. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/block-science/deterring-adversarial-behavior-at-scale-in-gitcoin-grants-a8a5cd7899ff. Accessed 2 June, 2021.

Buterin, V. “Review of Gitcoin Quadratic Funding Round 3”. 2019. Available online: https://vitalik.ca/general/2019/10/24/gitcoin.html. Accessed 31 May, 2021.

Ethereum Community Fund. “About ECT”. Available online: https://ecf.network/about/. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Ethereum Foundation. “Wishlist”. Ethereum Foundation. Available online: https://esp.ethereum.foundation/en/wishlist/. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Gitcoin. “WTF is QF”. Gitcoin. Available online: https://qf.gitcoin.co/?grant=&grant=&grant=&grant=&match=1000. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Gitcoin. Available online: https://gitcoin.co/. Accessed 3 June, 2021.

LAOCON. “NODE Tokyo 2018: Connecting Blockchain Community in Tokyo”. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/laocon/node-tokyo-2018-connecting-blockchain-community-in-tokyo-df94d8e297ca. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Larkin, B. “The Poetics and Politics of Infrastructure”. Annual Review of Anthropology. Vol. 42 (327-343). 2013. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

Latour, Bruno (2013) An inquiry into modes of existence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mehar, M., Shier, C., Giambattista, A., Gong, E., Fletcher, G., Sanayhie, R., Kim, H. M., and Laskowski, M. “Understanding a Revolutionary and Flawed Grand Experiment in Blockchain: The DAO Attack”. Journal of Cases on Information Technology. Vol. 21(1. 2017) 19-32., Doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3014782.

Nabben, K, & Zargham, M. “Permissionlessness”: exploring a commonly misconceived and convoluted term. Substack. Available online: https://kelsienabben.substack.com/p/permissionlessness-exploring-a-commonly. Accessed 1 June, 2021.

Nabben, K. (2021). “Blockchain Security as “People Security”: Applying Sociotechnical Security to Blockchain Technology”. Frontiers in Computer Science. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2020.599406.

OmiseGO. “Ethereum Community Fund”. OMG Network. Available online: https://omg.network/ethereum-community-fund/. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Owocki, K. “Introducing GTC – Gitcoin’s Governance Token”. Gitcoin blog. Available online: https://gitcoin.co/blog/introducing-gtc-gitcoins-governance-token/. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Plutarch. “Theseus”. MIT Classics. Available online: http://classics.mit.edu/Plutarch/theseus.html. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Rheingold, H. “Online Community Governance: Six Case Studies”. Patreon. 2021. https://www.patreon.com/posts/47388851. Accessed 01 May, 2021.

Rozas, D., Tenorio Fornés, A., Díaz Molina, S., & Hassan, S. (2021). When Ostrom meets Blockchain: Exploring the potentials of blockchain for commons governance. Sage Open 11 (1), pp. 1-14. Doi: 10.1177/21582440211002526.

Star, S. L. The Ethnography of Infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999): 377-391. doi:10.1177/00027649921955326.

Tantri, F. and Amir, S. “Modeling a Simulation for Sociotechnical Resilience.” Complexity, 1 (2019): 1-22, doi: 10.1155/2019/7950629.

Voshmgir, S. “Token Economy Book”. Github.https://github.com/Token-Economy-Book/EnglishOriginal. Accessed 01 May, 2021.

Walch, A. In Code(rs) We Trust: Software Developers as Fiduciaries in Public Blockchains. 2018. Chapter in Regulating Blockchain. Techno-Social and Legal Challenges, edited by Philipp Hacker, Ioannis Lianos, Georgios Dimitropoulos & Stefan Eich, Oxford University Press, 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3203198. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Werback, K (ed.). After the Digital Tornado. Cambridge University Press. 2020.

White, N. Blog. Available online: https://fullcirc.com/. Accessed 29 May, 2021.

Wikipedia, “Ship of Theseus”. Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ship_of_Theseus. Accessed 28 May, 2021.

Wikipedia. “Commons”. Wikipedia. Available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commons. Accessed 28 May, 2021.